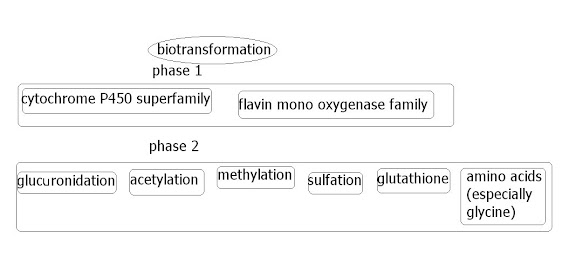

The xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes, or biotransformation enzymes (or probably other various names) are a very important group of enzymes in humans that are the main enzymes dealing with 'external' ('exogenous') chemicals, whether they be through food/drink, through the skin, breath etc. In effect, the frontline 'translators', translating the compounds into something the body knows what to do with. These enzymes can either detox something, or activate something (for instance the active compound in a medicine). They can be found in various places in the body, but are very concentrated in the liver, since this deals with blood purification etc. This group of enzymes can also detoxify internal ('endogenous') systemic chemicals, such as hormones/neurotransmitters etc; since, in the end, these sort of things are chemicals too.

The xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes, or biotransformation enzymes (or probably other various names) are a very important group of enzymes in humans that are the main enzymes dealing with 'external' ('exogenous') chemicals, whether they be through food/drink, through the skin, breath etc. In effect, the frontline 'translators', translating the compounds into something the body knows what to do with. These enzymes can either detox something, or activate something (for instance the active compound in a medicine). They can be found in various places in the body, but are very concentrated in the liver, since this deals with blood purification etc. This group of enzymes can also detoxify internal ('endogenous') systemic chemicals, such as hormones/neurotransmitters etc; since, in the end, these sort of things are chemicals too.

If you tend to handle a drug/medicine badly, a doctor will suggest an allergy is to blame. However, it is probably more likely to be a 'weakness' in one or more of the biotransformation enzymes. Drugs/medicines rely on these enzymes so heavily for activation or detoxication, that any weakness is thoroughly tested.Pharmacogenomics is the branch of pharmacology which deals with the influence of genetic variation on drug response in patients by correlating gene expression or single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a drug's efficacy or toxicity. By doing so, pharmacogenomics aims to develop rational means to optimise drug therapy, with respect to the patients' genotype, to ensure maximum efficacy with minimal adverse effects. Such approaches promise the advent of "personalized medicine"; in which drugs and drug combinations are optimized for each individual's unique genetic makeup.[1]

Pharmacogenomics is the whole genome application of pharmacogenetics, which examines the single gene interactions with drugs.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmacogenomics

In the case of FMO3, it is already known that some drugs tend to be heavy users (at least partly) of FMO3 enzyme. Ranitidine being an example. This would mean that anyone with a FMO3 weakness would likely handle ranitidine badly. Because FMO3 is so unresearched, it's probably early stages as to knowing what drugs use FMO3 enzyme heavily.

Another point is that it is probably early days as to knowing how many will have one or more FMO3 enzyme that is sub-optimal. Whereas mutant copies likely mean the % efficiency will be greatly reduced, variant copies may mean a slightly less efficient enzyme. However when the end product is that you smell out a room, its not much comfort even if you only have one or more variant copies. With Trimethylaminuria, patients are regarded as 'severe' or 'mild'. Probably as a rule, 'severe' means mutant copies and 'mild' means variants. At the moment the estimates of sub-optimal FMO3 function are probably grossly underestimated.

In the paper by Williams and Krueger recently posted, there was mention of a paper on a group of people taking a drug that involves FMO3. They suggest the FMO role in the detox of that drug was the likely 'weak link', and that 25% had to cease use of the drug due to side effects likely due to poor FMO3 function. At the moment we have crumbs to go on regarding this type of research, but if researchers were to look into this they may find 25% or more of the population could have an FMO3 weakness.Ethionamide (2-ethyl-4-thiocarbamoylpyridine) is structurally related to thiobenzamide and is being utilized in the treatment of tuberculosis. Recently, the laboratory of Dr. Paul Ortiz de Montellano demonstrated that ethionamide is a prodrug that must be S-oxygenated by an FMO in the target organism, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, to exert its effect (Vannelli et al., 2002). The metabolic activation of ethionamide by the bacterial FMO is the same as the mammalian FMO activation of thiobenzamide to produce hepatotoxic sulfinic and sulfinic acid metabolites. Not surprisingly, Dr. Ortiz de Montellano’s laboratory and our own have found ethionamide to be a substrate for human FMO1, FMO2, and FMO3 (unpublished observations). Approximately 25% of individuals have to discontinue ethionamide due to toxicity, primarily in liver, thought to be due to FMO3-dependent S-oxygenation. It would be of interest to determine if particular FMO3 allelic variants correlated to susceptibility to ethionamide hepatotoxicity.

There's a lot of 'ifs' and 'buts' involved in this post, but the main point was to highlight how reactions to medicines may be a sign of a biotransformation enzyme weakness (many of the population probably have one weakness of some sort), and also how because of lack of research, the incidence of FMO3 weakness (in practice) may be greatly underestimated.

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=15922018

Update : With hindsight, the researchers may in fact be suggesting an active FMO2 enzyme is to blame for the 25%. In most humans, FMO2 is naturally 'disabled' due to a nonsense mutation. But it is known now that a proportion may in fact have functioning FMO2. However the principle of the post is the same, in that those with FMO3 issues may be greatly underestimated.

If you go through these links and don't use MEBO on SMILE, MEBO will get ~4%

But ppl forget about these links ....so if u forget then choose MEBO in AMAZON SMILE

MEBO will get 0.5%

but 0.5% of something beats 4% of nothing

Amazon USA

Click here to Amazon USA

0 comments: